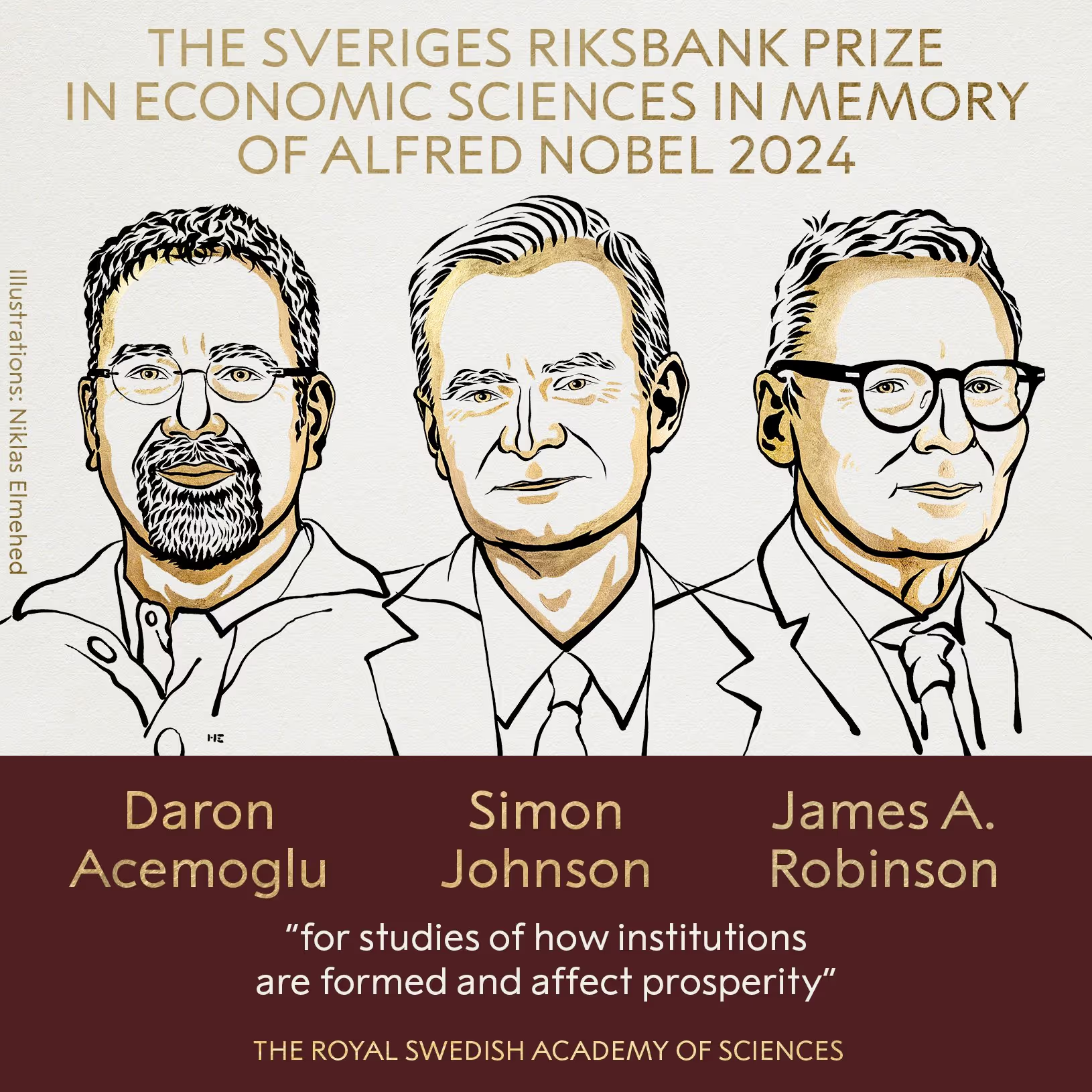

The recent awarding of the Nobel Prize in Economics to Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson highlights their influential work on the role of institutions in determining the prosperity of nations. Why Nations Fail underscores the importance of inclusive institutions and warns against the dangers of extractive systems. Power and Progress makes clear that societal change and prosperity are possible when the people push back against elites. These principles offer key lessons for Turkey's political and economic development, which has been facing a deepening crisis over the past decade.

In Why Nations Fail, Acemoglu and Robinson assert that institutions determine the economic outcomes of a nation. When they are inclusive—promoting accountability, participation, and the rule of law—societies become more equal and prosperous. However, when power is concentrated in the hands of a narrow elite and economic barriers prevent widespread participation, those societies remain poor and underdeveloped.

The authors trace this dynamic back to European colonization. In some regions, colonizers established exploitative systems that extracted resources from local populations, enriching only a small elite. This legacy, they argue, continues to shape the inequality seen in regions like Latin America, where colonial systems of exploitation still echo in modern economic structures.

Democratic countries rise thanks to the rule of law and the sanctity of private property, while nations with authoritarian or extractive political systems fall behind, regardless of the resources at their disposal. However, while the book effectively lays out this framework, it leans heavily on a form of institutional determinism. At times, the authors overlook the potential for transformative political movements or social upheaval to disrupt entrenched systems.

In Power and Progress, Acemoglu and Johnson examine the impact of technological advancements on inequality. They challenge the notion that progress automatically benefits everyone, arguing that technological gains often exacerbate inequality. The authors point out that the benefits that come with advancements are only distributed equitably to the masses when they get organized and push back against a narrow elite who may wield aristocratic, military, legal, or technological privileges.

Historical examples, such as the Industrial Revolution, demonstrate how technological progress can increase productivity while worsening conditions for the working class. In the early 19th century, while Britain’s industrialists thrived, others faced long working hours, stagnant wages, and poor living conditions. It took long decades of organized labor struggles to improve conditions for workers. Similarly, the invention of the cotton gin tremendously boosted cotton production in the early 1800s in the US, but also worsened the working conditions of slaves.

The authors assert that the productivity bandwagon happens on two conditions: increased labor productivity and bargaining power for labor. If one of these conditions is absent, progress is not shared with the rest of the population, and wealth accumulates in the hands of the few who hold power.

Inequality that came with the Industrial Revolution was reduced in the 20th century, especially after World War II during the boomer generation. Nonetheless, this trend has been reversed since the 1980s with the introduction of neo-liberal policies such as deregulation and deunionization. Moreover, a new revolution is underway: the digital era. The Big Five, which refers to Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft (GAFAM), now dominates about a fifth of the US economy. While wages have increased in the IT sector, they have stagnated or reversed across other sectors, especially for lower-income workers. In other words, Silicon Valley has now replaced the aristocratic elite of the Middle Ages, and the bourgeoisie of the Industrial Revolution.

Acemoglu and Johnson warn that the arrival of artificial intelligence, such as ChatGPT, in recent years could worsen inequality unless governments and workers push back. Machines should not serve as tools for mass surveillance and control, as seen in authoritarian regimes. Their solutions emphasize redirecting digital technology to complement human labor, not replace it.

On the other hand, while the authors praise Western Europe as a good student in incorporating human labor with technology, one should notice that Europe is falling behind other global powers, such as the U.S. In 2008, the eurozone's GDP was close to that of the U.S., but as of last year, the U.S. economy was approximately 80% larger, signaling Europe's struggle to keep pace.

In sum, the laureates underscore the distribution of wealth, power, and opportunity depends on the political and economic institutions in place, as well as the ability of the masses to organize and push for their fair share. Inclusive institutions distribute power broadly, ensure law and order, and secure property rights. They are the generator of the wealth. In contrast, extractive institutions concentrate power and resources in the hands of a few. They are bound to fail their people. Economic growth and technological advancements do not automatically lead to shared prosperity.

These principles offer key lessons for Turkey's political and economic development if it aims to overcome its current predicaments . The country has been sliding backward in all international indexes measuring the strength of the rule of law, economic development, equality, and basic freedoms compared to its peers over the last decade. The lessons from the laureates indicate that Turkey should build an inclusive system by upholding the rule of law to reverse its course.

Unlike the enthusiastic response to the previous Turkish Nobel laureate, Aziz Sancar, the Turkish government’s reaction to Daron Acemoğlu’s Nobel win has been mostly lukewarm so far, with the notable exception of Finance Minister Mehmet Şimşek. This initial reluctance may stem from the solutions he proposes for Turkey’s ongoing challenges.